Serenely Fast I/O Buffer (With Benchmarks)

Yet Another High-Performance Concurrent I/O Buffer

Intro

Nowadays, high-load services have to optimize network data transfer and move to an asynchronous model for sending and receiving. That way server is able to hold a message for the right time to submit. This introduces another bottleneck related to storing data in a buffer before sending. On the other hand, submitting small packets via TCP (which we are currently using) is slow.

Before talking about implementation, let's outline a few requirements for message buffer:

- FIFO (to preserve message order)

- Effectively unlimited size (the buffer needs to be expandable)

Related works

There are numerous implementations of message buffers: folly::IOBuf [1], absl::Cord [2], Seastar I/O buffer and even more in Go and Rust [3] libraries. However, we couldn't find the perfect one, since some of them do not support concurrent writes and reads, and others aren't that fast.

So, we've decided to reinvent the wheel and create yet another message buffer (and we've kinda done it). First, we will discuss our message buffer implementation, its API and internals, and then we will talk about benchmarks.

sdb::message::Buffer

Our approach presents a message queue, which supports concurrent writes and reads (with some limitations, which will be discussed later). Also, sdb::message::Message has terms such as committed and uncommitted data:

- Only committed data can be read from the message buffer.

- Uncommitted data cannot be followed by committed data (you cannot commit data without first committing the previous data).

It is mainly used to allow accumulating data before the reader can actually see it. For instance, the PostgreSQL protocol requires the size of the value before the actual value, so only after we write the whole value into the buffer, we then set the size and commit.

Another feature of the message buffer is Flush. While you are writing messages, you might have an urgent need to send messages because the buffer is getting too large or the message is crucial (an ACK message). So, in the message buffer's constructor, you can define a callback that the reader uses to send the data (for example, boost::asio::send). Also, on each write, you must explicitly set the need_flush variable:

need_flush = true– the message buffer will write, commit, and flush (send using the callback) all the data stored in the buffer.need_flush = false– the message buffer will write, commit, and flush only if the buffer exceeds the threshold.

Message types

Flushed data is urgent; it must be sent by the writer or by the reader (if the callback is finished and there is flushed data in the buffer). Only after calling FlushDone can the flushed data be erased.

Committed data is not urgent; it can be sent by the reader if the callback finishes and there is some committed data in the buffer.

Uncommitted data cannot be sent by the reader; it can be sent only after being committed.

You may ask: "And what about Nagle's algorithm? The socket will buffer urgent packets and our whole plan will fail". You are absolutely right! That is why we are using NO_DELAY in the boost::asio sending function. This approach allows us to control packet buffering and optimize network I/O.

Internals

sdb::message::Buffer is basically a linked list of chunks of data (sdb::message::Chunk); however, the read operation produces sdb::message::SequenceView, and with this wrapper, boost::asio::const_buffer can easily iterate over data chunks. The size of the chunks increases exponentially and is bounded by min_growth and max_growth.

Well, it is time to reveal the main secret: sdb::message::Buffer is SPSC (single-producer single-consumer) 😧. With such weak constraints, we have achieved the most efficient lock-free solution with the minimum number of atomic operations.

The buffer has only one atomic variable, _send_end; it defines the end of readable data (flushed or committed). So, it changes when the writer tries to flush more data or when the reader tries to read more committed data and send it using the callback:

void Buffer::FlushStart() {

SDB_ASSERT(_tail);

const BufferOffset tail_offset{_tail, _tail->GetEnd()};

// ...

if (_send_end.exchange(tail_offset, std::memory_order_acq_rel)) {

return;

}

SDB_ASSERT(!_socket_end);

// _socket_end - the end of flushing data

_socket_end = tail_offset;

SendData();

}

void Buffer::FlushDone() {

/* Free processed data */

// _socket_end - the end of flushing data

auto socket_end = std::exchange(_socket_end, {});

auto send_end = _send_end.load(std::memory_order_acquire);

if (send_end == socket_end &&

_send_end.compare_exchange_strong(send_end, BufferOffset{},

std::memory_order_acq_rel)) {

// We released "lock"/"ownership" here, so only local variables can be

// touched here

return;

}

_socket_end = send_end;

SendData();

}

In FlushDone, the reader tries to find committed but not flushed data, flush it, and move _send_end. By contrast, the writer tries to send only flushed data, so it competes with the reader to send flushed data. As you can see, there is a nice optimization trick to avoid a CAS operation when send_end == socket_end. In addition, memory_order is chosen as weakly as possible for maximum performance.

API

The API is pretty simple yet powerful:

class Buffer {

public:

Buffer(size_t min_growth, size_t max_growth,

size_t flush_size = std::numeric_limits<size_t>::max(),

std::function<void(SequenceView)> send_callback = {});

void WriteUncommited(std::string_view data);

void Write(std::string_view data, bool need_flush);

void Commit(bool need_flush);

/// Returns a pointer to a contiguous buffer with exactly `capacity` bytes.

/// The caller MUST write exactly `capacity` bytes to the returned buffer.

[[nodiscard]] uint8_t* GetContiguousData(size_t capacity);

/// Allocates a contiguous buffer with `capacity` bytes and invokes `op` to

/// write to it.

/// `op` receives a pointer to the buffer and MUST return the actual number of

/// bytes written. The buffer is resized to match the number of bytes actually

/// written by `op`.

template<typename Op>

void WriteContiguousData(size_t capacity, Op op);

};

While integrating the buffer, we found that in some cases it is crucial to have a contiguous data block. Therefore, we implemented GetContiguousData, which allocates a contiguous block of data and returns a raw pointer.

Evaluation

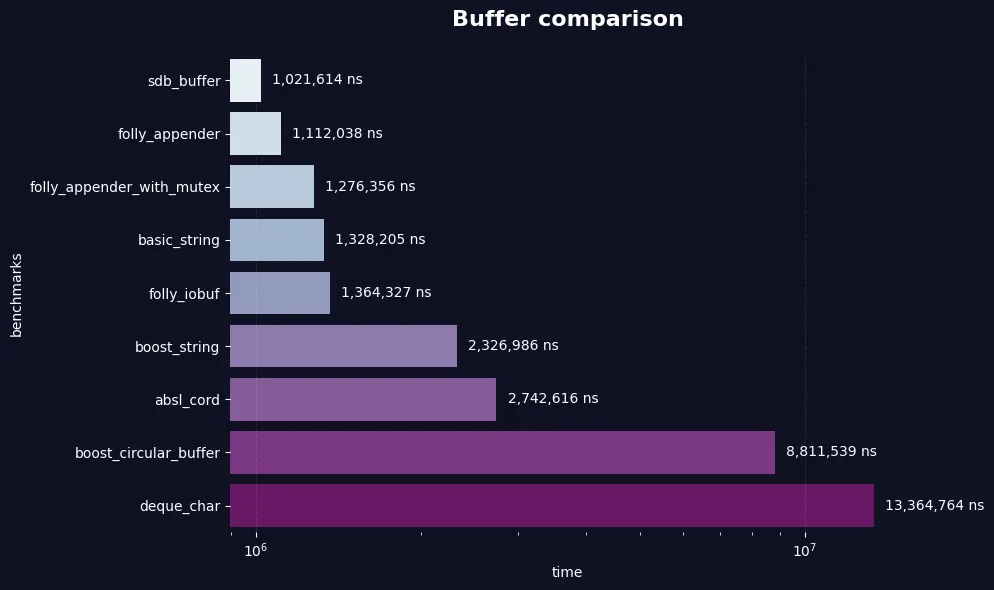

We wrote a benchmark for I/O buffers (folly, absl, and std::) [4]. Results:

As you can see, the folly appender and sdb buffer are the fastest message buffers. But what is the folly appender? Generally, it is the same as the folly IOBuf, but with exponential packet-size growth. In addition, we added the folly appender with a mutex implementation as the minimum required speed. So, let's dive even deeper and compare the folly appender (without a mutex) and sdb::message::Buffer!

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

WOW! sdb::message::Buffer seems to be faster than the folly appender in every case. Well, it ain't much, but it's honest work.

All the tests were run on an AMD Ryzen 9 9950X 16-Core Processor using jemalloc [5]. You can find the benchmark here: https://github.com/serenedb/serenedb/blob/main/tests/bench/micro/io_buffers.cpp

Results

As a result, we have a fast and efficient message buffer implementation that supports concurrent operations (with limitations). Notably, our solution doesn't have all the features of the folly library, but it has the bare minimum methods.

If you like performance optimizations as much as we do, then check out our GitHub repo: https://github.com/serenedb/serenedb (don't forget to star it 🤗).

You can also leave a comment in our Reddit group: https://www.reddit.com/r/serenedb/ — we’ll be glad to discuss it with you.

References

[1] `folly::IOBuf` and zero-copy networking. Lu Pan (2023). https://uvdn7.github.io/folly-iobuf-and-zero-copy-networking/

[2] Abseil Cord sources. https://chromium.googlesource.com/external/github.com/abseil/abseil-cpp/+/HEAD/absl/strings/cord.cc

[3] Tokio documentation. Module mpsc. https://docs.rs/tokio/latest/tokio/sync/mpsc/index.html

[4] Benchmarks. https://github.com/serenedb/serenedb/blob/main/tests/bench/micro/io_buffers.cpp

[5] jemalloc. https://github.com/jemalloc/jemalloc